I was delighted to have been able to attend a portion of the 8th UN Forum for Business and Human Rights. I have been reflecting on the lessons learned and the directions toward which that great assembly of states, enterprises, NGOs and academics would have us all journey.

That journey, of course, was wrapped up nicely in the 2019 Forum theme--Time to act: Governments as catalysts for business respect for human rights. For me, the theme produced a substantial irony, an irony that serves as the focus of the brief comments offered here on the state of the art in business and human rights and the perversity that it appears to foster as it lumbers along propelled by its own quite incomprehensible internal logic (at worst perhaps comprehensible in the sense that it fails to understand the consequences of the choices it appears to favor). It reminds us that ideological stances produce some time quite absurd results. And absurdity was the order of the day, at least for the positions taken by some of the leading states in this field.

My brief reflections are divided into two parts.

Part I (Reflections on the 8th U.N. Forum on Business and Human Rights--Part I, "Does Lesotho Exist?") was published first. It considered drive toward the legalization of the 2nd Pillar corporate responsibility actually produces a new sort of imperial system with human rights at its center and a confederation of --wait for it--states which formed the family of "civilized nations" as they were constituted in 1900 again appear take a leading position. For all other states there is, well, nothing. They disappear in the shadows of the sunshine cast by this Olympian cartel of states. The irony that appears to emerge out pf the 8th Forum in this respect that the drive to center the state actually divides states into those that count and those that are slated, effectively, for oblivion--resurrected only when necessary to hide the reality that the system of horizontal parity among states created after 1945 is being substantially transformed. Make no mistake, is not about Western privilege (though that trope is always useful in the corridors of Geneva, and New York or wherever it is deemed useful to manufacture a strategic reality for the voting masses); rather it is about power--the divide is between rich states from which global production is controlled or centered, and those states (the rest) whose people and resources serve them. And in the process, those serving states lose effectively their coherence as states (resurrected only for the photo-op sessi0ns that the UN system can ably arrange.

This Part 2--('Falling in Love Again:' 'Smart Mixes' and the De-Centering of the State Within Private Compliance Governance Orders') considers how the framework for this emerging imperium

actually has a far more interesting effect. The effect becomes more interesting when measured against the objectives expressed in the 8th Forum's theme. One would think, on the basis of the expected consequences of the building of vertically arranged power structures in which principal states oversee the economic activities (through their instrumentalities) of activities undertaken by them throughout their production chains, that the Forum theme would thereby be furthered. Here, at last, one might expect to see fulfilled the objectives that these states (and and dominant society intelligentsia) had sought for a long time. That would be a regulatory structure driven by the law of the most powerful states and enforced through their judicial structures, now serving the higher cause of (still badly defined) international human rights.

This Part 2--('Falling in Love Again:' 'Smart Mixes' and the De-Centering of the State Within Private Compliance Governance Orders') considers how the framework for this emerging imperium

actually has a far more interesting effect. The effect becomes more interesting when measured against the objectives expressed in the 8th Forum's theme. One would think, on the basis of the expected consequences of the building of vertically arranged power structures in which principal states oversee the economic activities (through their instrumentalities) of activities undertaken by them throughout their production chains, that the Forum theme would thereby be furthered. Here, at last, one might expect to see fulfilled the objectives that these states (and and dominant society intelligentsia) had sought for a long time. That would be a regulatory structure driven by the law of the most powerful states and enforced through their judicial structures, now serving the higher cause of (still badly defined) international human rights.

That journey, of course, was wrapped up nicely in the 2019 Forum theme--Time to act: Governments as catalysts for business respect for human rights. For me, the theme produced a substantial irony, an irony that serves as the focus of the brief comments offered here on the state of the art in business and human rights and the perversity that it appears to foster as it lumbers along propelled by its own quite incomprehensible internal logic (at worst perhaps comprehensible in the sense that it fails to understand the consequences of the choices it appears to favor). It reminds us that ideological stances produce some time quite absurd results. And absurdity was the order of the day, at least for the positions taken by some of the leading states in this field.

My brief reflections are divided into two parts.

Part I (Reflections on the 8th U.N. Forum on Business and Human Rights--Part I, "Does Lesotho Exist?") was published first. It considered drive toward the legalization of the 2nd Pillar corporate responsibility actually produces a new sort of imperial system with human rights at its center and a confederation of --wait for it--states which formed the family of "civilized nations" as they were constituted in 1900 again appear take a leading position. For all other states there is, well, nothing. They disappear in the shadows of the sunshine cast by this Olympian cartel of states. The irony that appears to emerge out pf the 8th Forum in this respect that the drive to center the state actually divides states into those that count and those that are slated, effectively, for oblivion--resurrected only when necessary to hide the reality that the system of horizontal parity among states created after 1945 is being substantially transformed. Make no mistake, is not about Western privilege (though that trope is always useful in the corridors of Geneva, and New York or wherever it is deemed useful to manufacture a strategic reality for the voting masses); rather it is about power--the divide is between rich states from which global production is controlled or centered, and those states (the rest) whose people and resources serve them. And in the process, those serving states lose effectively their coherence as states (resurrected only for the photo-op sessi0ns that the UN system can ably arrange.

This Part 2--('Falling in Love Again:' 'Smart Mixes' and the De-Centering of the State Within Private Compliance Governance Orders') considers how the framework for this emerging imperium

actually has a far more interesting effect. The effect becomes more interesting when measured against the objectives expressed in the 8th Forum's theme. One would think, on the basis of the expected consequences of the building of vertically arranged power structures in which principal states oversee the economic activities (through their instrumentalities) of activities undertaken by them throughout their production chains, that the Forum theme would thereby be furthered. Here, at last, one might expect to see fulfilled the objectives that these states (and and dominant society intelligentsia) had sought for a long time. That would be a regulatory structure driven by the law of the most powerful states and enforced through their judicial structures, now serving the higher cause of (still badly defined) international human rights.

This Part 2--('Falling in Love Again:' 'Smart Mixes' and the De-Centering of the State Within Private Compliance Governance Orders') considers how the framework for this emerging imperium

actually has a far more interesting effect. The effect becomes more interesting when measured against the objectives expressed in the 8th Forum's theme. One would think, on the basis of the expected consequences of the building of vertically arranged power structures in which principal states oversee the economic activities (through their instrumentalities) of activities undertaken by them throughout their production chains, that the Forum theme would thereby be furthered. Here, at last, one might expect to see fulfilled the objectives that these states (and and dominant society intelligentsia) had sought for a long time. That would be a regulatory structure driven by the law of the most powerful states and enforced through their judicial structures, now serving the higher cause of (still badly defined) international human rights.Yet, rather than returning power to the human rights imperial cartel states, it has the effect of dissipating that authority. States, effectively incapable of actually managing human rights through law, transform the role of law as a constituting element of legal orders that are actually delegated to enterprises (or better put delegated to the global production chains). As a consequence, the state itself disappears within the logic of the structures of its own approach to law into the vast data driven compliance machinery that the vanguard states have been furiously constructing (with the complicity of the largest enterprises) over the last generation.

My object remains the same as in Part I--to briefly sketch out one of the great absurdities of the current approach to the regulation of business and human rights--the great campaign of national regulation the results of which accelerate the process of privatizing law by governmentalizing the largest enterprises--delegating to them the functional role of the state in the management of the human rights effects of economic activities within global production. Perhaps that is as it should be. I have certainly been arguing this position since before many of the current crop of elite influence leaders learned to connect state-enterprise-human rights (e.g., From Moral Obligation to International Law; Geo. J. Int'l L 39(4):591-653 (2008)). But in the process, and in an effort--essentially reactionary--to revitalize the state as the source of control, and law as the language and structure through which such obligations are implemented, these "leading forces" of human rights change have essentially produced a mechanism through which the core power of the state will be obliterated, all the while preserving an increasingly fragile facade of state power.

Part II--Falling in Love Again:' 'Smart Mixes' and the De-Centering of the State Within Private Compliance Governance Orders'

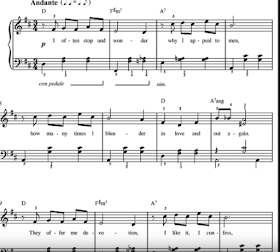

I often stop and wonder; Why I appeal to men

How many times I blunder; In love and out again

They offer me devotion; I like it, I confess

When I reflect emotion; There's no need to guess

Falling in love again; Never wanted to

What am I to do; I can't help it

Love's always been my game; Play it how I may

I was made that way; I can't help it

Men cluster to me; Like moths around the flame

And if their wings burn; I know I'm not to blame

Falling in love again; Never wanted to

What am I to do; I can't help it

(Orchestral Interlude)

Falling in love again; Never wanted to

What am I to do; I can't help it

Love's always been my game; Play it how I may

I was made that way; I can't help it

Men cluster to me; Like moths around the flame

And if their wings burn; I know I'm not to blame

Falling in love again; Never wanted to

What am I to do; I can't help it

(Transcribed by Mel Priddle - November 2013)

What am I to do; I can't help it

Love's always been my game; Play it how I may

I was made that way; I can't help it

Men cluster to me; Like moths around the flame

And if their wings burn; I know I'm not to blame

Falling in love again; Never wanted to

What am I to do; I can't help it

(Transcribed by Mel Priddle - November 2013)

-->

In the 1930 German film Der Blaue Engel (The Blue Angel), based on Heinrich Mann's 1905 novel Professor Unrat (Professor Garbage) a conventional high school teacher (Professor Rath, played by Emile Jennings) descends from the heights of conventional respectability to the role of cabaret clown and madness in the orbit of the cabaret's dancer Lola Lola (played by Marlene Dietrich) with whom is has had a short affair that ruins him. The signature song that captures the film's zeitgeist, Ich bin von Kopf bis Fuß auf Liebe eingestellt" (Falling in Love Again) (music and lyrics by Friedrich Hollaender), nicely captures the relationship between the state (as Professor Rath)--conventional and bound by the rules that gives his essence meaning--and the markets based UNGP 2nd Pillar as the foundation of regulatory governance (Lola Lola) whose by being herself p`roves both irresistible to and the undoing of the good professor.

But of course, the UN Forum is not the cabaret to which those standard bearers of respectability--the state--are drawn and seduced by the freedom it offers from the convention that binds states tighter than a sealed drum. Nor is the 2nd Pillar if the UNGP our Lola Lola, against which our good professor (states) have been warning their students (global enterprises), and the protection of whose respectability has drawn states to the cabaret in which Lola Lola is encountered. States have not become the cabaret clowns of the UN Forum; nor has the UNGP 2nd Pillar and its portal opening to regulatory governance (for a discussion, see Theorizing Regulatory Governance Within Its Ecology) made the state pathetic and an object of ridicule by its students and the society that expected better.

But there are some resonances made clearer when one steps back for a second from the sometimes turgid and interest-laden discursive tropes that mark these sorts of conversations for the clarity of a song lyrics written well before the idea of globalization of the sort encountered today could even have risen to the level of science fiction. What that clarity provides is an insight. It is not that the state has humiliated itself by abandoning law in succumbing to the allure of the UN GP 2nd Pillar and the framework of regulatory governance. Rather it is that the embrace by states of compliance-accountability-monitoring-reporting structures has turned law into a form of cabaret clown, whose own performance now makes it impossible for the state to remain respectable through law. It is in "Falling in Love Again" with law, that the societal sphere is again able to transform what had once been its master into little more than the accounting house, the auditors--through which it can retain its legitimacy with its global constituency. In the process, of course, law becomes constitutive rather than normative, and the state, again, loses its centering (at least conventionally understood) position in the cosmology of power relations in global production. Of course our Lola, the markets at the core of the global production chain, would just laugh and say, "Falling in love again; Never wanted to; What am I to do; I can't help it."

For those who find this too esoteric (precisely because the analogies are meant to rip the reader from the insides of the leaden discursive tropes inside of which the respectable tend to argue these things, within the bounds of propriety), perhaps seeing gthe emerging role of the state through the lens of the Swedish Trade Minister, Anna Halbewrg, will drive the point home.

Here, the emerging role of the state sector in the governance of the human rights consequences of business activities emerges clearly.

First, the state embraces, as it should, a 1st Pillar UNGP "commitment to protect and fulfil human rights." Yet that commitment to protect and fulfill is undertaken through a leadership role. Consider what that means in terms of both the mechanics of leadership (politics) and its characteristics (politics and structural baselines). Political parties, and vanguard elements of social forces undertake leadership roles. Leninist parties are tasked with guiding the state and administrative apparatus. But in this area, states are viewed primarily as the nexus of the highest expression of sovereign (and thus legitimate--a point NGOs in favor of the Comprehensive treaty never tire of reminding the rest of us) authority--law. That was the point of the 1st Pillar in large respect--to remind states of their duty to undertake through their own domestic legal orders the substantive duties they had embraced (to the extent they felt like it) of their international obligations along with or as a supplement to the human rights structures already framed within their constitutional orders. That, however, is not what the Swedish Trade Minister has in mind. In place of law, she centers (as she must) the techniques of regulatory governance, of markets, and in the process de-centers the state (and law) as a normative foundation. In its place, a "smart mix" shifts normative and operational authority to the enterprise (along with the international community as the generator of norms, not binding on the state but rather on the operations of its enterprises) leaving the state in the role of the celestial clockmaker charged with the great but remote task of defending the integrity of the system it oversees. She does this in seven steps.

Second, social dialogue is an odd basis on which to build the State duty. It acquires an even odder position as the first of the principles of state leadership in a context in which communities seeking to defend rights holders have been clamoring for law--substantive law and law permitting a moire realistic access to justice. It is that clamoring that has produced the rights holder protective (though in a sadly poor way, see, e.g., here) demand for a Comprehensive business and human rights treaty. And this approach appears to disappoint. Indeed, this is the sort of thing one would expect to be at the heart of the 2nd Pillar--and ridiculed there. But here it appears to acquire a loftier standing. Perhaps that is because dialogue with the state is best; but that would be an odd conclusion for a human population for whom the state is a novel concept and hardly ever in accord with societal realities. Aaaah, but dialogue here is meant to substitute or supersede the democratic process. That ought to give the populations of liberal democratic states pause. Does Pillar 1 permit the blatant (it has of course been inherent for a century or so) aristocratic tendency in the actualities of liberal democratic governance,. Again, and again, one sees the reflex toward treating the objects of good intentions as without capacity (like children). They have no power. And this part of the speech makes that clear enough. Now transpose this pattern to the one that dominates discourse among states. . . . . What one has is an invitation to dialogue based on power. And an embrace of the principle that within the mechanisms of states, the object (lawmaking) is a product of the sort of deal making in the shadow of substantive norms that is, in fact, the essence of the derided (as unaccountable) 2nd Pillar.

Third, the tendency to identify with the "causes of the month" produces the sort of sloganeering that, when produced by Marxist Leninist regimes, induces substantial criticism among the liberal democratic states whose representatives now appear unable (in turn) to resist. Sweden is a feminist state. . . Really? That is what is offered. It might have been more useful to suggest both what feminism means--hopefully as an inclusive rather than an invertive power/culture principle. Sweden has something to offer here, though none of it was in evidence. That, in part, is because much of the advances have come from the governmentalization of the private sector which has been given the laboring oar in developing the regulatory structures to make a robust feminism a reality--one wirth national characteristics (a discussion that this speech avoids).

Fourth, corruption is an area where the state has much to offer. That started, of course, with the Americans in the 1970s, with the world slowly catching up as this, too, became popularized through the normative developments (backed by loan terms) of the International Financial Institutions and their public lending policies. Bur still. And yet here, the centrality of the state and of law is deceptive. Anti-corruption efforts have indeed been profoundly transformative. But the transformation is essentially a consequence of compliance not directly of law. It is to compliance systems--and thus to the governmentalization of the global administration of the enterprise within the jurisdictional boundaries of its activities, that one looks to the development both of the systems of rules to combat corruption, and its implementation. That state stands aside. . . it judges, it evaluates, it holds accountable--like an electorate in a liberal democratic state. It protects the system within which such private governmentalized systems can operate, but it does not govern directly. pr

Fifth, the reference to global value chains makes the point. This is the operationalization of public (state driven) cultures that would make small states like Lesotho as irrelevant, and indeed as obstacles, to the proper running of global production--one grounded in the sensibilities that are better developed and transmitted from European, Western and Asian capitals, than from the sweat shop states of the world (e.g., Reflections on the 8th U.N. Forum on Business and Human Rights--Part I, "Does Lesotho Exist?").

Sixth, the National Action Plans. I have had little good to say about National Action Plans; and that has put me on the wrong side of the herd (see, e.g., here). I hope someday to be proven wrong; I expect that will be a task fraught with the likelihood of failure. What National Action Plans have wrought has been the usual tendency to export norms and compliance outward, with a sometimes substantial wall between domestic human rights regimes and those reserved for work undertaken "abroad." But worse, in this case, and I thank the Swedish Minister for being so open, is the inherent issues of hegemony that the National Action Plan project has been engendering. Just as it went without notice that the Norwegian Pension Fund Global and its US NGO Consultant could effectively treat Lesotho as nonexistent with respect to human rights harms occurring within its territory, so Sweden can speak to the way that it helps capacity poor states develop appropriate NAPS to suit the times and their direction. For those who started off life in the global South, the spectacle of parading the Thai's around as an example of a success might not have brought Sweden the reaction it thought it was entitled to obtain for this "good work." But worse, these NAPS also center their work on compliance--that is they delegate responsibility to the private sector to actually do the work. And in the process accelerate the movement of regulatory power (and control) from the state to the 2nd Pillar enterprises.

Seventh, sustainability reporting is to be welcomed. And indeed, the entire project of fusing the human rights, climate change, and sustainability projects is long overdue. But a combination of turf protection and inertia (regulatory and administrative drag as well) plagues this project. Still it was warming to see it mentioned. But less warming to see it fractured along national lines. Sustainability os not a state project; climate change does not change its character at the borders of states. And yet a program that creates incentives toward national programs might have perversely bad effects. But that is not what they are after. Putting this point together with the previous, what one sees here is an effort to use what Professor Ruggie references as "leverage" (see below in this essay), by seeking to legislate the framework within which enterprises will develop global governance regimes the baseline of which will be determined by the regulatory framework of the regulating (usually home) state. Here again one sees a 1st Pillar power assertion bounded by its ability to activate 2nd Pillar power.

Eighth, SOEs remain an important element of 1sdt Pillar power. But in essence, given the ideology of OECD states, more a 2nd Pillar issue. Here one deals with the state as shareholder--another aspect of privatization. And one deals with the public role of state projections of power in private markets--again bounded by OECD ideologies. And yet, what the state applies to its own enterprises as a shareholder could as easily be applied to all of its enterprises as legal expectations. The gap is more an affectaiotn than a reality--and yet a useful one for states reluctant to legislate.

Ninth, investment strategies. Here Sweden can do a lot of good. But that good is as a bank with a public conscience. Again, the Minister speaks the language of compliance, and it undertakes implementation through the markets driven world of lending. One is back in the world of the 2nd Pillar with the state as a powerful partner. But it is the world of the 2nd Pillar none the less.

And, indeed, the eight points of the Swedish minister points to the fundamental problem of the 8th Forum theme: a truly robust 1st Pillar would effectively require the abandonment of markets in fgavor of central planning regimes. Ironically, the only states in the global now capable of a profoundly robust engagement with the 1st Pillar are Cuba and North Korea. To embrace the market--as global actors have robustly embraced it over the last generation to build the current trade order--is to have to acknowledge that ti has produced a great transformation int he role of the state, and the role of law in the management of economic activity now organized along global production chains. "Smart mix" in that context inevitably leads aeway from the effective deployment of the ideology of the state around which the mythologies of the 1st Pillar are built.

As John Ruggie recently perhaps inadvertently underlined in his much read and important Keynote Address Conference on Business and Human Rights: Towards a Common Agenda for Action Organized by Finland’s Presidency of the EU Council:

What all of these movements toward “smart mixes” and legal pluralism signify,

What the trajectory toward the governmentalization of the private sphere and the legalization of its governance;

What the centering of the state as the administrative unit overseeing structures of accountability beyond its ability to directly regulate by traditional means;

What the mix that is at the heart of the re-branded 1st Pillar strategy appears to be is this:

For those who find this too esoteric (precisely because the analogies are meant to rip the reader from the insides of the leaden discursive tropes inside of which the respectable tend to argue these things, within the bounds of propriety), perhaps seeing gthe emerging role of the state through the lens of the Swedish Trade Minister, Anna Halbewrg, will drive the point home.

“Stepping up government leadership: from commitments to action”. Minister for Trade Anna Hallberg’s speech in the opening plenary of the 2019 UN Forum on Business and Human Rights. November 25th, 2019.

Excellencies, distinguished guests, ladies and gentlemen, I am very pleased to be with you today at this important meeting. The United Nations Forum on Business and Human Rights concerns matters close to my heart: the respect and promotion of human rights in the business sector.

I have spent almost my entire life in the business sector and was appointed Sweden’s minister for trade three months ago. Therefore, it is extra special for me to talk about governments as a catalyst for business respecting human rights.

I am here today because Sweden’s government has a strong commitment to protect and fulfil human rights and fully support this theme for the forum. Let me share with you seven key areas for the Swedish government’s work.

I will start with social dialogue. In 2016, the Swedish Prime Minster initiated the Global Deal partnership. The Global Deal is a multi-stakeholder partnership hosted by the OECD in collaboration with ILO, promoting an enhanced social dialogue. We believe this is crucial to foster decent work and quality jobs globally. By extension, we believe it contributes to greater equality and inclusive growth.

In Sweden we can see that almost everyone benefits from increased trade and open global markets. We have a social security system that is engineered for coping with change. For example, if a company decides to close its operations at a factory, our answer is not mainly to try to stop it, but to handle the consequences in a way that protects the workers and the society.

Change is not a threat – it’s an absolute necessity! But status quo and locking in old production methods is a threat to any company and any state.

We have a social safety net that steps in. We offer retraining so that workers can find new jobs in more profitable and modern sectors.

Thanks to this system, Swedish trade unions are pro-change and pro free trade. We have strong unions and our Swedish businesses want strong unions. They appreciate unions as partners of the social dialogue. This partnership between employers and employee organizations has also been a key factor behind many successful Swedish companies.

Workers win by gaining influence, improved working conditions and better opportunities for education and social welfare.

Companies win from a constructive working atmosphere, an openness to change, increased productivity and stronger consumers.

Society wins from inclusive growth and social stability.

It’s a win-win-win situation. I call upon other states, organizations and companies to join the Global Deal initiative.

The second area is feminism. The Swedish government is a feminist government. We emphasize the human rights of all women and girls as absolutely essential for sustainable economic development. This is not just the right thing to do. It also makes sense economically. Gender inequality is always wasteful.

The third area is corruption. For the Swedish government the fight against corruption and bribery is key to sustainable development and the fulfillment of the Agenda 2030. Corruption is devastating for the business sector and for societies. Companies are less interested in investing in countries or regions with widespread corruption. This blocks economic development and undermines democracy.

Governments have a responsibility to build strong institutions, support the rule of law, and implement legislation on anti-corruption. In the Swedish Government’s Drive for Democracy, an initiative aimed at responding to recent threats and challenges to democracy, fighting corruption is an important component.

The fourth area is Global Value Chains. Global value chains are a key component of the globalized economy, and they must be sustainable in all their parts. A chain is only as strong as its weakest link. In global trade, a chain of production can only be considered responsible and sustainable if it is so every step of the way.

We believe the Agenda 2030 presents a golden opportunity to gather the private sector to further develop ways to ensure that these global value chains respect human rights.

The fifth area is National Action Plans. It is essential for every country to implement and follow up National Action Plans for Business and Human Rights, in order to implement the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights. Sweden supports countries in Asia and the Pacific in this regard. I am pleased to see that Thailand has developed a National Action Plan and I would like to congratulate Thailand on being the first country in Asia to adopt a Plan.

The Swedish National Action Plan, launched in 2015, was followed-up in 2018 with a report on recommendations. Now, we are taking the National Action Plan one step further by launching a Swedish Platform for International Sustainable Business. We want to further improve our work in this field by developing one unified platform for Government initiatives.

The sixth area is about Sustainability Reporting. The EU demands sustainability reporting for all companies having more than 500 employees. We have strengthened this requirement in our national legislation. In Sweden, we require all companies having 250 employees or more to provide a sustainable development report.

This was important to spark change and awareness in an initial phase. But today many Swedish businesses are proactive and have placed sustainability in their core business model. They now have extensive sustainability reporting – beyond legislation requirements – to boost the companies’ business and shareholder value.

Consumers demand socially responsible production and companies take own initiatives to improve sustainability. Government action was necessary as a catalyst of change, but when the demand comes from consumers and markets it gets so much stronger.

The seventh area is state-owned companies, which must be role models in terms of sustainable business. The Swedish government has therefore made human rights an integral part of the corporate governance of Swedish state-owned enterprises by strengthening the follow-up of the UN’s guiding principles. We have introduced crystal clear requirements in the state ownership policy, skill-enhancing measures and improved tracking of the companies’ work in this field.

Lastly, our government will soon launch our new Export- and Investment Strategy. When we devised this strategy, it was clear to us that Sustainable Business would have to be at its absolute core. Sweden wants to show that trade is compatible with sustainability and respect for human rights. Sustainability is not an obstacle for trade, it will enhance trade.

A sustainable business sector, with human rights as a corner stone, is absolutely necessary for any country’s future welfare.

Thank you!

Here, the emerging role of the state sector in the governance of the human rights consequences of business activities emerges clearly.

First, the state embraces, as it should, a 1st Pillar UNGP "commitment to protect and fulfil human rights." Yet that commitment to protect and fulfill is undertaken through a leadership role. Consider what that means in terms of both the mechanics of leadership (politics) and its characteristics (politics and structural baselines). Political parties, and vanguard elements of social forces undertake leadership roles. Leninist parties are tasked with guiding the state and administrative apparatus. But in this area, states are viewed primarily as the nexus of the highest expression of sovereign (and thus legitimate--a point NGOs in favor of the Comprehensive treaty never tire of reminding the rest of us) authority--law. That was the point of the 1st Pillar in large respect--to remind states of their duty to undertake through their own domestic legal orders the substantive duties they had embraced (to the extent they felt like it) of their international obligations along with or as a supplement to the human rights structures already framed within their constitutional orders. That, however, is not what the Swedish Trade Minister has in mind. In place of law, she centers (as she must) the techniques of regulatory governance, of markets, and in the process de-centers the state (and law) as a normative foundation. In its place, a "smart mix" shifts normative and operational authority to the enterprise (along with the international community as the generator of norms, not binding on the state but rather on the operations of its enterprises) leaving the state in the role of the celestial clockmaker charged with the great but remote task of defending the integrity of the system it oversees. She does this in seven steps.

Second, social dialogue is an odd basis on which to build the State duty. It acquires an even odder position as the first of the principles of state leadership in a context in which communities seeking to defend rights holders have been clamoring for law--substantive law and law permitting a moire realistic access to justice. It is that clamoring that has produced the rights holder protective (though in a sadly poor way, see, e.g., here) demand for a Comprehensive business and human rights treaty. And this approach appears to disappoint. Indeed, this is the sort of thing one would expect to be at the heart of the 2nd Pillar--and ridiculed there. But here it appears to acquire a loftier standing. Perhaps that is because dialogue with the state is best; but that would be an odd conclusion for a human population for whom the state is a novel concept and hardly ever in accord with societal realities. Aaaah, but dialogue here is meant to substitute or supersede the democratic process. That ought to give the populations of liberal democratic states pause. Does Pillar 1 permit the blatant (it has of course been inherent for a century or so) aristocratic tendency in the actualities of liberal democratic governance,. Again, and again, one sees the reflex toward treating the objects of good intentions as without capacity (like children). They have no power. And this part of the speech makes that clear enough. Now transpose this pattern to the one that dominates discourse among states. . . . . What one has is an invitation to dialogue based on power. And an embrace of the principle that within the mechanisms of states, the object (lawmaking) is a product of the sort of deal making in the shadow of substantive norms that is, in fact, the essence of the derided (as unaccountable) 2nd Pillar.

Third, the tendency to identify with the "causes of the month" produces the sort of sloganeering that, when produced by Marxist Leninist regimes, induces substantial criticism among the liberal democratic states whose representatives now appear unable (in turn) to resist. Sweden is a feminist state. . . Really? That is what is offered. It might have been more useful to suggest both what feminism means--hopefully as an inclusive rather than an invertive power/culture principle. Sweden has something to offer here, though none of it was in evidence. That, in part, is because much of the advances have come from the governmentalization of the private sector which has been given the laboring oar in developing the regulatory structures to make a robust feminism a reality--one wirth national characteristics (a discussion that this speech avoids).

Fourth, corruption is an area where the state has much to offer. That started, of course, with the Americans in the 1970s, with the world slowly catching up as this, too, became popularized through the normative developments (backed by loan terms) of the International Financial Institutions and their public lending policies. Bur still. And yet here, the centrality of the state and of law is deceptive. Anti-corruption efforts have indeed been profoundly transformative. But the transformation is essentially a consequence of compliance not directly of law. It is to compliance systems--and thus to the governmentalization of the global administration of the enterprise within the jurisdictional boundaries of its activities, that one looks to the development both of the systems of rules to combat corruption, and its implementation. That state stands aside. . . it judges, it evaluates, it holds accountable--like an electorate in a liberal democratic state. It protects the system within which such private governmentalized systems can operate, but it does not govern directly. pr

Fifth, the reference to global value chains makes the point. This is the operationalization of public (state driven) cultures that would make small states like Lesotho as irrelevant, and indeed as obstacles, to the proper running of global production--one grounded in the sensibilities that are better developed and transmitted from European, Western and Asian capitals, than from the sweat shop states of the world (e.g., Reflections on the 8th U.N. Forum on Business and Human Rights--Part I, "Does Lesotho Exist?").

Sixth, the National Action Plans. I have had little good to say about National Action Plans; and that has put me on the wrong side of the herd (see, e.g., here). I hope someday to be proven wrong; I expect that will be a task fraught with the likelihood of failure. What National Action Plans have wrought has been the usual tendency to export norms and compliance outward, with a sometimes substantial wall between domestic human rights regimes and those reserved for work undertaken "abroad." But worse, in this case, and I thank the Swedish Minister for being so open, is the inherent issues of hegemony that the National Action Plan project has been engendering. Just as it went without notice that the Norwegian Pension Fund Global and its US NGO Consultant could effectively treat Lesotho as nonexistent with respect to human rights harms occurring within its territory, so Sweden can speak to the way that it helps capacity poor states develop appropriate NAPS to suit the times and their direction. For those who started off life in the global South, the spectacle of parading the Thai's around as an example of a success might not have brought Sweden the reaction it thought it was entitled to obtain for this "good work." But worse, these NAPS also center their work on compliance--that is they delegate responsibility to the private sector to actually do the work. And in the process accelerate the movement of regulatory power (and control) from the state to the 2nd Pillar enterprises.

Seventh, sustainability reporting is to be welcomed. And indeed, the entire project of fusing the human rights, climate change, and sustainability projects is long overdue. But a combination of turf protection and inertia (regulatory and administrative drag as well) plagues this project. Still it was warming to see it mentioned. But less warming to see it fractured along national lines. Sustainability os not a state project; climate change does not change its character at the borders of states. And yet a program that creates incentives toward national programs might have perversely bad effects. But that is not what they are after. Putting this point together with the previous, what one sees here is an effort to use what Professor Ruggie references as "leverage" (see below in this essay), by seeking to legislate the framework within which enterprises will develop global governance regimes the baseline of which will be determined by the regulatory framework of the regulating (usually home) state. Here again one sees a 1st Pillar power assertion bounded by its ability to activate 2nd Pillar power.

Eighth, SOEs remain an important element of 1sdt Pillar power. But in essence, given the ideology of OECD states, more a 2nd Pillar issue. Here one deals with the state as shareholder--another aspect of privatization. And one deals with the public role of state projections of power in private markets--again bounded by OECD ideologies. And yet, what the state applies to its own enterprises as a shareholder could as easily be applied to all of its enterprises as legal expectations. The gap is more an affectaiotn than a reality--and yet a useful one for states reluctant to legislate.

Ninth, investment strategies. Here Sweden can do a lot of good. But that good is as a bank with a public conscience. Again, the Minister speaks the language of compliance, and it undertakes implementation through the markets driven world of lending. One is back in the world of the 2nd Pillar with the state as a powerful partner. But it is the world of the 2nd Pillar none the less.

And, indeed, the eight points of the Swedish minister points to the fundamental problem of the 8th Forum theme: a truly robust 1st Pillar would effectively require the abandonment of markets in fgavor of central planning regimes. Ironically, the only states in the global now capable of a profoundly robust engagement with the 1st Pillar are Cuba and North Korea. To embrace the market--as global actors have robustly embraced it over the last generation to build the current trade order--is to have to acknowledge that ti has produced a great transformation int he role of the state, and the role of law in the management of economic activity now organized along global production chains. "Smart mix" in that context inevitably leads aeway from the effective deployment of the ideology of the state around which the mythologies of the 1st Pillar are built.

As John Ruggie recently perhaps inadvertently underlined in his much read and important Keynote Address Conference on Business and Human Rights: Towards a Common Agenda for Action Organized by Finland’s Presidency of the EU Council:

The conference agenda asks the question: How do we most effectively advance action on the EU level? My job this morning is to sketch out the backstory to our discussions and suggest some strategic directions.Professor Ruggie gets this partially right. And perhaps that is necessarily an inevitable consequence of an approach that has, to a necessary extent, continued to seek to center the state—understood as the community of states as horizontally equal partners--but in reality nudging toward the use of the 1st Pillar as the cover under which the home states of the great global production chains can (as he suggests) use their leverage to develop regulatory chains extending down into and obliterating any sense of partnership among states (see Part I of these reflections here: Reflections on the 8th U.N. Forum on Business and Human Rights--Part I, "Does Lesotho Exist?").

Let me begin with the most basic question: what is business and human rights all about? The answer varies depending on vantage point. In big-picture terms, it is about the social sustainability of globalization. . . .

When seen from the perspective of enterprises, business and human rights is about ways they can recover trust and manage the risk of harmful impacts. Undeniable progress has been achieved by individual firms, business associations, and even sports organizations. But not enough, and not by enough of them.

For governments, business and human rights is at the core of new social contracts they need to construct for and with their populations. This includes decent work and living wages, equal pay for work of equal value, social and economic inclusion, education suitable to the needs and opportunities of the 21st century, and effective social safety nets to buffer unexpected shocks to the economy or the person.

For the individual person whose rights are impacted by enterprises, business and human rights is about nothing more – but also nothing less – than being treated with respect, no matter who they are and whatever their station in life may be, and to obtain remedy where harm is done.

My second point is to remind us that formal international recognition of business and human rights as a distinct policy domain is relatively recent. At the UN level, the first and thus far only formal recognition dates to 2011, when the Human Rights Council unanimously endorsed the Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights.. . . .

That brings me to the key issue of strategy – how to reinforce and add to this transformative dynamic. The Guiding Principles embody two core strategic concepts: advocating a “smart mix of measures,” and using “leverage.” I’ll take them up in turn.

We often hear the term “smart mix of measures” being employed to mean voluntary measures alone. But that gets it wrong. Guiding Principle 1 says that states must have effective legislation and regulation in place to protect against human rights harm by businesses. Guiding Principle 3 adds that states should periodically review the adequacy of such measures and update them if necessary. They should also ensure that related areas of law, for example corporate law and securities regulation, do not constrain but enable business respect for human rights. So, a smart mix means exactly what it says: a combination of voluntary and mandatory, as well as national and international measures.

A number of EU member states and the EU as a whole have begun to put in place mandatory measures that reinforce what previously was voluntary guidance to firms on corporate responsibility. These include reporting requirements regarding modern slavery, conflict minerals, and non-financial performance more broadly, as well as human rights and environmental due diligence. Such initiatives are aligned with the spirit of the UNGPs, and they are important steps in adding “mandatory measures” into the mix. Still, many leave a lot to the imagination – of company staff, consulting firms, and civil society actors among others. More should be done to specify what meaningful implementation looks like, in order to avoid contributing to the proliferation of self-defined standards and storytelling by firms. Also, with limited exceptions currently no direct consequences follow from non-compliance. Nevertheless, the ascent of Pillar I is underway.

What all of these movements toward “smart mixes” and legal pluralism signify,

What the trajectory toward the governmentalization of the private sphere and the legalization of its governance;

What the centering of the state as the administrative unit overseeing structures of accountability beyond its ability to directly regulate by traditional means;

What the mix that is at the heart of the re-branded 1st Pillar strategy appears to be is this:

The focus on the state (with exceptional variations for the "great states" the U.S. and China, and with a "moral exception for the incarnation of internationalization that the EU continues to hope to represent) is not meant to amount so much to the centering of the state within the 1st Pillar of the UNGP. Instead it heralds the triumph of the 2nd Pillar and its capture of the state in ways that are palatable to the ideologies of conventional state supremacy (at least among those states already subject to the "leverage" of the "big 3"--US-China-EU). The object, again, is to keep those at the bottom happy withg, and to offer a hopeful rationalization, of their (inevitable) position in global power chains. For that, at the end, is all there is.

And here again we come to the great insight that can be derived from The Blue Angel: at the end, neither Professor Rath nor Lola Lola can be anything but what they are. And that is what they will be. But the students, the cabaret goers, the orchestra, that is all those who shift between gymnasium and cabaret, those who work in and for the cabaret and the gymnasium, those who function in the society around which professor, dancer, and students can rationalize their lives, those who make use of Rath and Lola Lola, it is to those that the emerging social order belongs. And to be somewhat tiresome about the meaning: In a world in which one accepts the primacy of international law and the compulsion of international norms (however manifested to the extent they have societal weight), but which also is profoundly tied to the state as the apex source of politic al legitimacy, and yet recognizes the realities of governance through enterprises that may be c constituted to mirror the state and which may be called up on to develop bin ding regulatory structures, and compliance mechanisms extending down their chain of control and up to the states to which they might be held accountability for the quality of their legal structures and the efficacy of their implementation, the state must cede both its regulatory primacy and its role as the center of the institutional framework for the management of global business.

That is the vision that our Swedish Trade Minister and John Ruggie would appear to have us embrace. That is also a vision profoundly at odds with the traditional reading of the 8th Forum’s theme. But perhaps, the view of Lola Lola, “can’t help it.” The alternative, of course, is not Lola Lola, but that very European avatar of itself--Lulu. It is to that which I will turn to in discussing the next generation state based mandatory due diligence laws.

-->And here again we come to the great insight that can be derived from The Blue Angel: at the end, neither Professor Rath nor Lola Lola can be anything but what they are. And that is what they will be. But the students, the cabaret goers, the orchestra, that is all those who shift between gymnasium and cabaret, those who work in and for the cabaret and the gymnasium, those who function in the society around which professor, dancer, and students can rationalize their lives, those who make use of Rath and Lola Lola, it is to those that the emerging social order belongs. And to be somewhat tiresome about the meaning: In a world in which one accepts the primacy of international law and the compulsion of international norms (however manifested to the extent they have societal weight), but which also is profoundly tied to the state as the apex source of politic al legitimacy, and yet recognizes the realities of governance through enterprises that may be c constituted to mirror the state and which may be called up on to develop bin ding regulatory structures, and compliance mechanisms extending down their chain of control and up to the states to which they might be held accountability for the quality of their legal structures and the efficacy of their implementation, the state must cede both its regulatory primacy and its role as the center of the institutional framework for the management of global business.

That is the vision that our Swedish Trade Minister and John Ruggie would appear to have us embrace. That is also a vision profoundly at odds with the traditional reading of the 8th Forum’s theme. But perhaps, the view of Lola Lola, “can’t help it.” The alternative, of course, is not Lola Lola, but that very European avatar of itself--Lulu. It is to that which I will turn to in discussing the next generation state based mandatory due diligence laws.

No comments:

Post a Comment