The global ordering continues to move vigorously forward in its transformation from a qualitative to a quantitative system. If it cannot be measured, it may not be authenticated. And if it may not be authenticated, then it is either less legitimate or effectively ungovernable. The old systems grounded in rules curated by administrative organs and enforced by the prosecutorial powers of the state--effectively an exogenous system of governance--has been giving way to an endogenous system. Endogenous systems are measurable, they are built in the shadow of an ideal against which the quantification of the distance between ideal and contemporary operation serves as the means through whicvh conduct may be made accountable. Endogenous systems are systems of accountability (see here); and accountability systems are grounded in administrative cultures of compliance.

For such systems, the measurement of performance serves a critical function. And the politics of collective organizations shifts from the space occupied by elected officials in the organs of state to the coders, analysts and systems administrators whose choices effectively legislate both the compliance ideal and the means by which measurement of the distance between actual performance and the ideal is taken. They are also the key actors in determining the consequences of that measurement. Yet that can also be the problem--not of the project of quantified governance, but in the larger political problem of assessment as a function of values/objectives. Politics, then, is shifted in two directions--outward with respect to the way that values are assigned to assessed data process through analytic--and downward with respect to the choice and quality of the data harvested, as well as the data ignored. The quantification may be politics free, but virtually everything related to its production is the essence of politics, of culture, and of social choices that then seek to bend numbers to their vision of the way things ought to be, and be seen by others. This is the essence of a scientific semiotics, in which meaning is a self-reflexive product of the choices for its quantification.

|

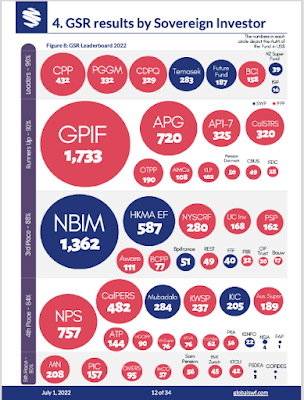

| Pix Credit here; p. 12 |

The recently released 2022 GSR Scoreboard for State Owned Investors nicely captures these trajectories and their challenges. It provides a valuable quantification of the sovereign investor master narrative embedded within the ideal of public actors operating as private enterprises on a level playing field across national borders with a principal objective to make money on investment opportunities. One interesting finding overall: "As highlighted before in this report, pension funds are much better run than sovereign funds when it comes to governance, sustainability, and resilience. Within SWFs, those sourced from commodity earnings (mostly oil and gas) score better in transparency, accountability and legitimacy, while those sourced from foreign exchange reserves are generally more responsible investors." (Ibid., p. 24)

The GSR Scoreboard is comprised of 25 different elements, 10 of them related to Governance issues, 10 of them related to Sustainability issues, and five related to Resilience issues. These questions are answered binarily (Yes / No) with equal weight based on publicly available information only, and the results are then converted into a percentage scale for each of the funds. The study is applied to a universe of the world’s Top 100 SWFs and Top 100 PPFs (“Global SWF’s Top 200”), generating 5,000 data points, and repeated annually. (2022 GSR Scoreboard for State Owned Investors p. 30 App. 3).

At the same time, deviation also begins to outline those sovereign investors who might be playing by different rules--and thus to develop a better sense of their operations and priories as it affects investment markets. One can measure this against the orthodox consensus ideal, or against the principles under which these outliers operate (and at the same time develop a better understanding of the effects of these deviations on performance as well as on the integrity of a global economic system grounded in private markets driven transactions.

The Executive summary follows.

Global SWF is a financial boutique that was launched in July 2018 to address a perceived lack of thorough coverage of State-Owned Investors (SOIs), including SWFs and PPFs, and to promote a better understanding of, and connectivity into and between global investors. The company leverages unique insights and connections built over many years and functions as a one-stop shop for some of the most common SOI-related services. (2022 GSR Scoreboard for State Owned Investors p. 33 App. 4)

Executive SummaryMain findings of the assessmentWe are delighted to present our 2022 GSR Scoreboard, the most comprehensive analysis yet on the governance, sustainability and resilience practices by State-Owned Investors around the world.

The GSR Scoreboard was first introduced by the Global SWF team in 2020 as an assessment tool for the best practices of certain institutional investors, including sovereign wealth funds and public pension funds. We believe that important aspects such as transparency and accountability, responsible investing, and legitimacy and long-term survival are not mutually exclusive and must be considered jointly.

The scoring is based on 25 different elements: 10 related to governance, 10 to sustainability, and five to resilience. These questions, which have not changed since 2020, are answered binarily (Yes/No) with equal weight based on publicly-available information only, and then converted into % points. The system is rigorous, quantitative, and fully independent, as the funds in question do not pay any membership fee to be assessed.

The 2022 edition introduces three main changes:

We have doubled our coverage from the world’s Top 100 State-Owned Investors (70 SWFs / 30 PPFs) to the world’s Top 200 SOIs (100 SWFs / 100 PPFs), generating a total of 5,000 datapoints for this analysis.

For public pension funds, we now take into consideration the funding flows and status of the main depositor, e.g., for Dutch fund APG, we would look at ABP to answer questions relative to the funding scheme.

All the assessed funds have been informed of their preliminary scores with at least a month of notice, so that they can study them and point us to any information missing, or to complement them with public links.

These changes have had a positive impact on the overall results: the sample now benefits from having more PPFs, which normally present higher scores; we have been able to answer questions around funding which we could not before; and several funds have been able to improve their results. The last point is especially important, as it highlights the benefits of having such independent and quantifiable system in place.

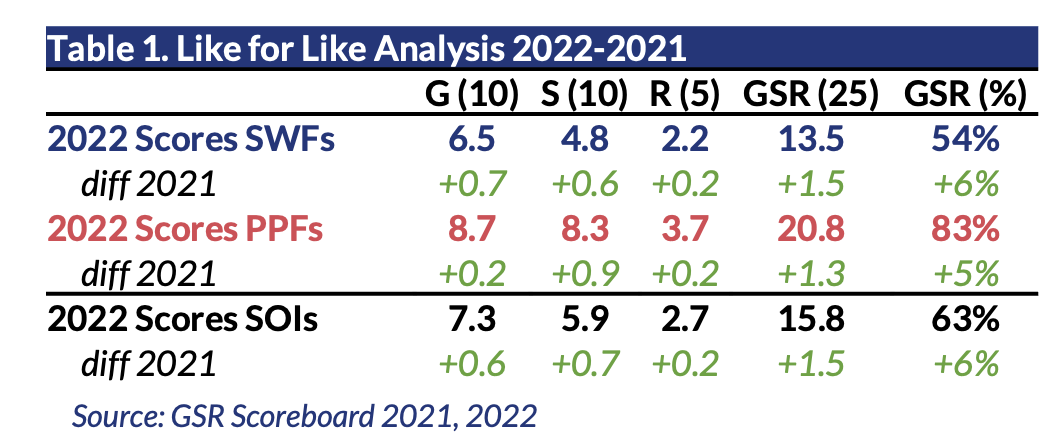

The results of the 2022 study, therefore, would look overly optimistic if compared to 2021. Even if we only consider the SOIs rated last year and undertake a “like-for-like” analysis, we observe a considerable improvement: sovereign wealth funds have improved 6%, and public pension funds, 5%.

“State-Owned Investors are increasingly focused on enhancing their ESG frameworks and capabilities”

This year we did not have a single winner but eight: four SWFs and four PPFs. The largest is Canada’s CPP Investments, which failed to score full marks due to just one point relating to its structure. We spoke with the fund’s CIO about best practices. See our chat in pag.17-18.

NZ Super and ISIF are great ambassadors for New Zealand and Ireland, respectively, and ensure a strong score at country-level. The former has one of the most robust governance standards among SWFs, and the latter was designed with a resilient and thorough fiscal rule.

Two regions saw several improvements: the GCC, led by Qatar’s QIA, Abu Dhabi’s Mubadala, and Saudi’s PIF; and Sub-Saharan Africa, led by Angola’s FSDEA, Gabon’s FGIS and Senegal’s FONSIS. However, MENA remains the region with the worst score, 46%.

Pension funds continue to display better marks than sovereign funds across the board, especially when it comes to governance and sustainability. However, resilience is not their forte and there are many US retirement pools that have precarious funding status and drag down the “R” rating in the scorecard.

Among the 100 SWFs assessed, the 20 stabilization funds are usually very liquid pools of capital that need to respond to fiscal deficits, so sustainability is not normally too high on the agenda. On the flip side, the 50 strategic funds analyzed are generally well placed when it comes to sustainability issues given their role in their domestic economies but may present a weaker framework around legitimacy and liquidity risk.

Lastly, the 30 savings funds are a mixed breed and some incorporate stabilization and/or development elements, which makes the analysis more challenging. But some of them have also improved significantly since last year, including some of the largest Middle Eastern funds of similar name: ADIA, KIA, LIA, and QIA.

No comments:

Post a Comment