|

| Pix credit here |

The United Nations as designated 27 January as International Holocaust Remembrance Day (IHRD). Within a more complicated context for the living, one full of ironies and reversals, and as a means engaging in acts of memory, posted below please find the (1) UN Statement on the 2025 observance; (2) the US Mission to the United Nations Remarks at Holocaust Memorial Ceremony 2025; and (3) a most interesting and perhaps provocative (in its neutral sense of provoking thought) essay by Jan Gerber recently posted to Telos Insights. Each in its own way recalls the cognitive cages of memory and the pathways to remembering.

UN

Theme: Holocaust Remembrance for Dignity and Human Rights

2025 marks 80 years since the end of the Second World War and the Holocaust.

Eighty years ago, in response to the atrocities of the war and the Holocaust, governments of the world established the United Nations, pledging to work together to build a just world where human rights were enshrined, and all could live with dignity, in peace.

Acknowledging the milestone year, the Holocaust and the United Nations Outreach Programme has chosen as its guiding theme for 2025, “Holocaust remembrance and education for dignity and human rights”.

The theme reflects the critical relevance of Holocaust remembrance for the present, where the dignity and human rights of our fellow global citizens are under daily attack.

The Holocaust shows what happens when hatred, dehumanization and apathy win.

Its remembrance is a bulwark against the denigration of humanity, and a clarion call for collective action to ensure respect for dignity and human rights, and the international law that protects both.

Holocaust remembrance safeguards the memories of survivors and their testament of life before the Holocaust – of vibrant communities, of traditions, of hopes and dreams, of loved ones who did not survive.

Safeguarding the history brings dignity to those the Nazis and their collaborators sought to destroy.

Remembrance of the Holocaust is a victory against the Nazis and their collaborators, and against all who would try to continue their legacy through spreading hatred, Holocaust distortion and denial into the 21st century.

* * *

Ambassador Dorothy Shea

Chargé d ’Affairs ad interim

New York, New York

January 27, 2025

AS DELIVERED

Thank you to all the survivors and family members present today, including Ms. Ginger Lane, Mr. Dumitru Miclescu, and Ms. Marianne Muller. It is a true privilege to be here with you. Thank you for sharing your stories of persecution, but also of perseverance.

It is one thing to read about the Holocaust in a book. It is another thing to hear about it from someone who lived it. That human connection really makes a difference. It deepens our understanding of the darkest of moments in human history, on a personal level. And it strengthens our resolve to live up to the sacred promise “Never Again.” So, thank you all.

I also want to thank Secretary-General Guterres, President Yang, Under-Secretary-General Fleming, and all of those esteemed representatives and guests who are with us today to commemorate International Holocaust Remembrance Day.

The theme of this gathering “Holocaust Remembrance for Dignity and Human Rights” serves as a reminder of how hatred, dehumanization, and apathy can lead to genocide. And it underscores the importance of calls for collective action to prevent the spread of hatred and denial of the Holocaust.

2025 – as we have heard – marks the 80th anniversary of the end of World War II and the liberation of the Nazi concentration and death camps that were some of the main sites of the genocide of six million Jews known as the Holocaust.

The United Nations General Assembly designated January 27, the anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz-Birkenau in 1945, as International Holocaust Remembrance Day, a time to remember the six million Jewish victims of the Holocaust and the millions of other victims of Nazi persecution. We are here today to recognize the importance of commemorating this day and the extraordinary courage of the victims and survivors of the Holocaust.

For survivors of the Holocaust, returning to a dignified life was vital. Every day, we have a moral obligation to honor that struggle, to honor the victims, learn from the survivors, and carry forth the lessons of the century’s most heinous crime.

We are continually and painfully reminded that hate doesn’t go away, it only hides. And it falls to each of us to speak out against the resurgence of antisemitism and ensure that bigotry and hate receive no safe harbor. At home and around the world, we must promote dignity and human rights in the face of the continuing scourge of antisemitism.

Unfortunately, despite these efforts, today we see the rise of antisemitism and other forms of hatred globally.

Holocaust denial and distortion are also on the rise. They are a form of antisemitism and are often coupled with xenophobia. History shows, as hatred directed at Jews rises, violence and attacks on the foundations of democracy are not far behind.

It is vital that we confront this problem at this moment. The Anti-Defamation League (ADL) recently released Global 100 Survey, which highlights significant trends and areas of concern regarding antisemitic [attitudes] worldwide. It was conducted in 103 countries and territories. According to this survey, 46 percent of adults harbor elevated levels of antisemitic sentiment. This represents an estimated 2.2 billion people worldwide, marking the highest level since the ADL began tracking these trends over a decade ago.

The data also highlights a troubling increase in antisemitic attitudes among younger demographics, with significant implications for future societal dynamics.

Holocaust distortion is now 13 percentage points more prevalent than Holocaust denialism. Although the survey has no specific data on the exact cause of this, ADL experts believe that social media and new malicious variations of mis- and disinformation are playing a major role in Holocaust distortion.

Despite these alarming statistics, the results also show global acknowledgment of antisemitism as a pressing issue, with the majority recognizing it as a serious problem. This presents a crucial opportunity for governmental action and policy intervention to combat these biases effectively.

We urge the endorsement and implementation of the Global Guidelines for Countering Antisemitism, already embraced by scores of nations and organizations, as an essential step toward mitigating the scourge of global antisemitism.

The United States also embraces the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance’s Working Definition of Antisemitism, inclusive of its examples.

As a founding member of the 35-member International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance, we encourage the IHRA’s Recommendations for Teaching and Learning About the Holocaust.

The challenge now lies in putting these guidelines into practice. The UN must demonstrate its full commitment to its human rights mandate and take concrete steps that will lead to tangible progress. Together, we can make a difference. Together, we can stamp out hate.

Atrocities like the Holocaust don’t just happen. They are allowed to happen. It is up to us to stop them. Never again.

I thank you.

###

* * *

|

The following text is based on a lecture given by the author at the event series “‘Das ganze Grauen’: Psychoanalytische Aufklärung nach dem 7. Oktober” [“‘The Whole Horror’: Psychoanalytic Enlightenment after October 7”] in July 2024 at the International Psychoanalytic University (IPU) Berlin.Translated by Julius Bielek.

1

In terms of world politics, 1978 was not a particularly outstanding year. The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and the second oil price shock both cast their shadows forward, but developments in the Middle East and on the oil markets only came to a head in 1979. Yet like many other years of lesser significance in terms of world politics, 1978 stands out in cultural history. Historical experiences are not only processed by art, culture, and science but are also sometimes anticipated in a distorted form. For example, Anthony Burgess’s 1978 novel 1985 gives the impression that not only the Iranian Revolution but also the power struggle between Margaret Thatcher and the trade unions had already taken place—albeit with the opposite result.¹

Much more significant than Burgess’s late work, however, are two other new releases from 1978: Edward Said’s Orientalism was first published by Pantheon Books;² and, around the same time, Marvin J. Chomsky’s miniseries Holocaust was broadcast on the television channel NBC.³ Said’s book is rightly regarded as the founding manifesto of postcolonial studies; Holocaust is a key event in the history of the impact of mass destruction. Of course, there had been minor waves of discussion of the extermination of European Jews even before it was shown—for example, in the context of the Eichmann trial in 1961 or the Frankfurt Auschwitz trial from 1963 to 1965. In the strict sense, however, remembrance of the Holocaust only began with this TV miniseries in the 1970s.

At first glance, the release of Orientalism and the broadcast of Holocaustappear to have little in common. The emergence of postcolonial studies was closely linked to the economic rise of Africa, Latin America, and Asia—the Trikont. By cutting oil production in 1973, the Arab OPEC states had confidently plunged East and West into a deep crisis; around the same time, the Asian tiger economies—South Korea, Singapore, Taiwan, and Hong Kong—were taking off economically.

Postcolonialism, in other words, is not only the voice of the subaltern and the marginalized, but also an expression of the emerging self-awareness of the non-Western world. Similar to traditional European historiography, it also has the function of ideological self-assurance: where do we come from, where are we going? With its help, the catastrophes of the past are reappraised, claims on the future are historically legitimized, and, not to be forgotten, some of the negative developments of the present—dictatorship, kleptocracy, failed states—are justified by reducing them, as Axelle Kabou and George Ayittey emphasized early on,⁴ to the afterlife of colonialism. Beyond all the justified criticism of colonialism and global inequality, postcolonial studies are thus also accompanying ideological instruments of the competitive struggle on the world market.

The interest in the Holocaust since the late 1970s, on the other hand, was due not least to the end of the postwar boom and the first major phase of détente in the Cold War. The memory of the destruction of European Jews had been at odds with both the optimistic belief in a better future and the fear of the atomic bomb that had characterized the economic miracle of the 1950s and 1960s. Those who believe they have no tomorrow do not deal with the past, but at most with the present. When both historical optimism and the antinomian catastrophe consciousness associated with it eroded in the 1970s, the view of the past was cleared. Generational changes and the increased importance of human rights during this period did the rest.

Even if Orientalism and Holocaust seem to have little in common on superficial examination, there are links between the rise of postcolonial theory and the beginning of the period of remembrance of the Nazi mass extermination. They are at least partly connected with the almost obsessive accusations of postcolonial so-called “scholar-activists,” against the acknowledging of the unprecedented, distinctive character of the Holocaust, and against Israel. Of particular importance here is a process that I would describe as the dialectic of victimhood.

2

It is well known that until the 1970s, the memory of National Socialism and the Second World War was determined not by the Holocaust but by the events at the front or within the Maquis underground. This was certainly also due to the fact that the struggle, martyrdom, and even torture there were more comprehensible to the general public as commensurate with past experience than was extermination for its own sake. The idea of a meaningless death was almost unbearable in view of continued life after 1945.

At the same time, however, and directly related to this, the figure of the innocent, defenseless, and passive victim, which the Germans had produced by the millions, did not fit with the role model of the prudent hero, who takes his fate into his own hands in a manner that is as stoic as it is dutiful. This role model had certainly been called into question by the First World War at the latest, which, despite Ernst Jünger’s heroic tales, had nothing heroic about it. Even mass society, which may have occasionally fueled the yearning for individual heroism, demonstrated its impossibility on a daily basis: the experiences of powerlessness and humiliation that it constantly produces are the opposite of heroism. Yet because the role model of the hero had been firmly anchored in the occidental imaginative world since at least Homer, it continued to live on beyond its refutation.

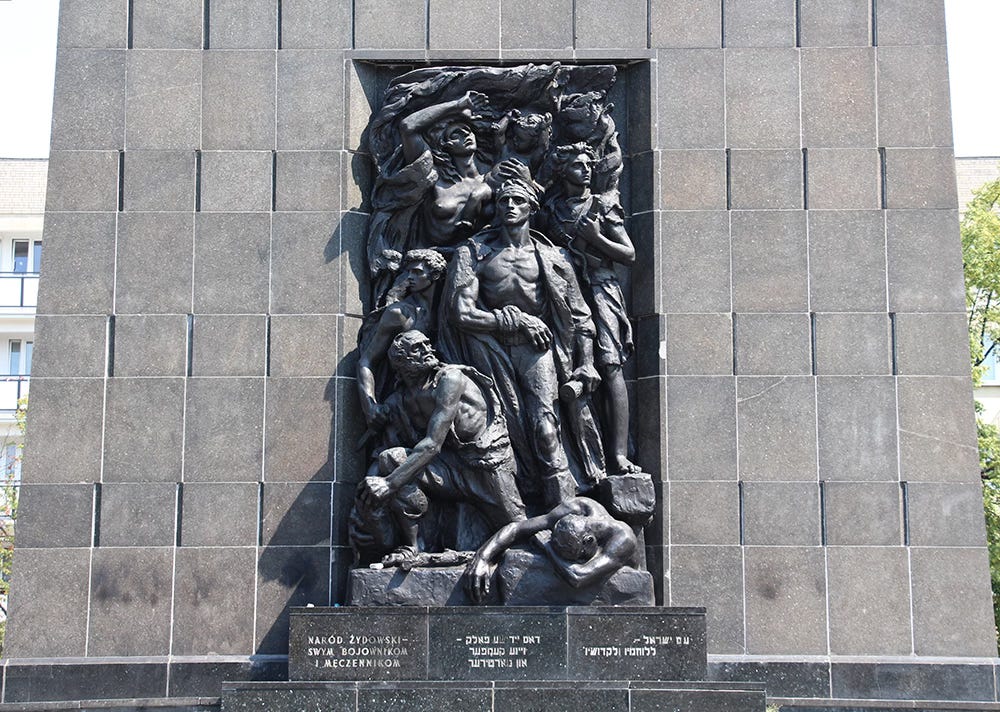

This was probably one of the reasons why the story of the 1943 Warsaw Ghetto Uprising was told not only by many communists, who subscribed to Progress and the Future, but also—at least in this respect not dissimilar to them—by Zionists as a heroic drama. Even Marek Edelman, one of the commanders of the uprising, initially followed this pattern. Although he always insisted that he had not changed his assessment over time,⁵ after the war he cultivated the combative optimism that he later repeatedly criticized. In his first memoir, Getto walczy (The Ghetto Fights), published in Warsaw by the General Jewish Labor Bund in 1945,⁶ he still employed some traditional, pathos-laden formulas of heroism: “Once again the fighters celebrate their second complete victory . . . . Every house is fighting.” The volume ends with the words that the fallen had “fulfilled their task to the end, to the last drop of blood.”⁷

The longevity of such heroism, as expressed in these words, was soon to be met with the historical optimism of the first postwar decades. On both sides of the Iron Curtain, the life-supporting measures consisted of full employment, technological progress, and mass consumption. They were merely weighted differently in the East and West—and were incorporated into different ideological images. In the Soviet sphere of influence, there was the socialist hero, who could be called Ernst Thälmann, Yuri Gagarin, or Imre Muszka; in the West, it was the self-made man, who in the 1950s and 1960s often wore a cowboy hat and rode off into the sunset on the cinema screen.

Yet the sense of impending doom that accompanied the optimism for the future like a shadow—remember the atomic bomb—was also reflected in art and the culture industry: recall the theater of the absurd or film noir. Even so, traditional heroic concepts can occasionally be found there as well. Even the central slogan of convalescent heroism comes from one of the darkest Westerns of the time. In High Noon (1952), Fred Zinnemann and Carl Foreman put those famous words into the mouth of their actor Gary Cooper, which soon became a familiar catchphrase: “A man’s gotta do what a man’s gotta do.” The silent hero remained both a cultural icon and a forward-looking role model.

In contrast to the hero, the figure of the innocent and defenseless victim—the “victimus,” as it is called in Latin, in contrast to the “sacrifare” of the voluntary sacrifice—was long frowned upon. This also applies to Israel, where hundreds of thousands of persecuted people had found a new home. This is one of the reasons why the appearance of Yehil De-Nur, a survivor of Auschwitz, during the Eichmann trial in the Jewish state in 1961, evoked not only compassion but also shame. De-Nur, who had written some of the first books about the Holocaust under the pseudonym Ka-Tzetnik 135633, broke down during his testimony in court. His daughter remembers that since then she has been regarded everywhere as “the daughter of the fainter.”⁸

The collective shame sparked by De-Nur’s collapse certainly had a distinctly Israeli dimension as well. It should be understood not least against the background of the efforts at demarcation from the galut [exile] that characterized the young state: for many of its intellectual leaders, Zionism was a counter-image to the supposed weakness of Diaspora. At the same time, however, the unease that accompanied the powerlessness of the witness was part of the general distance from victims that was cultivated during this period.

As the work of historian Svenja Goltermann has shown, the image of the innocent and passive victim only began to emerge in the late nineteenth century.⁹ Its emergence was due in no small part to attempts to “civilize” war and to distinguish between legitimate and illegitimate violence. Nevertheless, the figure of the victim was associated with shame well into the second half of the twentieth century; victims were met with reservations. They were regularly blamed for their own suffering, sometimes through their own actions, sometimes through certain mental dispositions.

3

This changed at the turn of the 1970s. During this period, social role models changed, as Christopher Lasch pointed out long ago.¹⁰ There were many reasons for this, too. Initially, they had little to do with the memory of the Holocaust. A central role was instead attributed to the end of Fordism, as the long-dominant production regime of standardized assembly line production, mass consumption, and social welfare is often called. Its decline, which had been emerging since the late 1970s, was closely linked to the transformation of industrial societies into service societies. The hard-working industrial worker, whose iconography incorporated at least some residues of classical heroic representations, was disappearing, at least as a general trend.

Moreover, other developments contributed to the changing perception of heroes and victims. The oil crises of 1973 and 1979 pushed economically driven historical optimism, which had shaped the postwar decades alongside the atomic bomb, to its limits. As a result, the Western notion of the self-made man eroded, as did the image of the socialist hero. Since the 1970s, no new heroic role models or figures of identification have emerged east of the Iron Curtain, as had been the case in previous decades. The “end of the grand narratives” that Jean-François Lyotard spoke of around the same time took care of the rest.¹¹

|

With all these changes, the figure of the hero certainly did not completely disappear from the public sphere. As a cultural icon, it continues to be present, albeit often caricatured or “taken ironically,” as the saying goes. The victim itself also did not become a social role model, as is occasionally claimed. Nevertheless, the dual turn from stoicism to sensitivity and from silence to cathartic communication, which took place during this period, contributed to a stronger interest in experiences of suffering and their evaluation. As Peter Novick pointed out a few years ago, society’s relationship to victims has shifted: “the cultural icon of the strong, silent hero is replaced by the vulnerable and verbose antihero. Instead of enduring in silence, one lets it all hang out. The voicing of pain and outrage is alleged to be ‘empowering’ as well as therapeutic.”¹²

It was also against this background that the questions raised earlier by some American, European, and Israeli psychiatrists about the long-term effects of experiences of violence soon received more attention; this is another reason why veterans of the Vietnam War, unlike the GIs who had fought in Korea only twenty years earlier, came together in self-help groups to fight against medical and social prejudice against victims. In 1977, a year before the first broadcast of Holocaust, post-traumatic stress disorder was mentioned for the first time—a diagnosis that did not exist before.

The fields of law and criminology also turned more to the victims than before. While the young branch of victimology, a subfield of criminology, was still being denounced as a “fad” in the 1960s,¹³ it rose to become an internationally recognized discipline in the following decade. In September 1973, shortly before the outbreak of the Yom Kippur War, the “First International Symposium on Victimology” took place in Jerusalem; congresses in Boston and Münster followed. In 1979, the year in which Holocaust was first shown in the Federal Republic of Germany and Austria, the World Society of Victimology was founded, and it still exists today.

It was not least due to this increase in the social significance of the victim that the Holocaust received greater attention. The extermination had long been overshadowed by the battle, but the relationship was soon reversed: while in the 1950s and 1960s even high-quality historical studies on the Second World War had sometimes made do without any mention of the Holocaust, the extermination was now sometimes told without any reference to the war, which had after all formed its context.

This also applied to the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, which for a long time had been both the counter-image and the representative of the memory of the Holocaust. Since the 1970s, the number of newspaper and magazine articles published about it has decreased in both the East and the West. The books that appeared about the uprising were soon overshadowed by the almost unmanageable literature on the Holocaust. Directly related to this, the heroism in the works about the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising also generally disappeared.

Hanna Krall’s literary conversations with the aging Marek Edelman, which were published at the end of the 1970s under the title Shielding the Flame, serve as a symbol and a manifesto of this development. There, the figure of the hero gets almost entirely dismantled. Edelman, who had himself narrated the uprising as a heroic drama just thirty years earlier, now refused to engage in any pathos or sensemaking. In particular, his statements about Mordechaj Anielewicz, the leader of the Jewish Combat Organization, amounted to a toppling of a monument. Edelman remembered him not as a shining hero but as a brave youth with fears, worries, mistakes, and foibles. When Krall asked him why Anielewicz had been appointed commander, he replied succinctly: “He very much wanted to be a commander, so we chose him. He was a little childlike in this ambition, but he was a talented guy, well read, full of energy.”¹⁴

In contrast to his statements in 1945, Edelman now seemed to admire the insurgents less than those who were deported to the extermination camps. “It’s terrible when someone goes to their death so calmly,” he explained, referring to the tens of thousands who had gathered at the Umschlagplatzholding area around the ghetto’s train station during the so-called liquidation of the Warsaw Ghetto in 1943. “It’s harder than any shooting, it’s much easier to die shooting. How much easier it seemed for us to die than for the people who had to get into the cattle wagon, go on this journey, dig their grave, undress stark naked.”¹⁵ In short, as interest in the experiences of victims grew, contributing to a greater awareness of the Holocaust, extermination took precedence over fighting.

4

This increased significance of the social figure of the victim also contributes to the emergence of postcolonialism, at least in part. The anti-colonialism inherited by postcolonialism and the memory of decolonization in the young nation-states of the 1950s and 1960s were also primarily oriented toward heroic narratives. The best example is Gillo Pontecorvo’s 1966 The Battle of Algiers, a film that depicts events from the Algerian War of Independence. It is much better than some of its fans might suggest: Andreas Baader, co-founder of the German left-wing terrorist group Red Army Faction, is said to have considered The Battle of Algiers his favorite film; Edward Said called it among “the two greatest political films ever made.”¹⁶

Even though The Battle of Algiers was financed by Algeria, it is not a propaganda film. Despite his sympathies for the FLN, Pontecorvo endeavored to “be fair to both sides,” as a film critic once wrote.¹⁷ The Battle of Algiers also shows the excesses of the FLN, the Algerian National Liberation Front, including the well-known bomb attack on a café in the European-influenced part of Algiers in July 1957, in which eleven civilians were murdered.

Nevertheless, Pontecorvo concentrated on the exchange of blows between the two warring parties, France and the FLN. If he gave greater space to victims, it was not the defenseless and innocent “victimus” but the voluntary self-sacrifice of the “sacrifare”: shortly before the end of the film, one of the heroes, Ali La Pointe, together with other FLN members, refuses to surrender. They do not want to leave the hideout to which they have retreated. As a result, the house where the hideout is located is blown up. La Pointe and his comrades-in-arms, among them a child, appear as fighters and martyrs. The film ends with stirring crowd scenes that are aimed toward the future.

Although the concept of martyrdom also became part of postcolonialism, in contrast to anti-colonialism it is based less on a hero narrative than on a victim narrative. As a result of the rise of the social figure of the victim, not only the persecution and extermination of the European Jews but also other experiences of suffering and persecution have received more attention since the 1970s than before. Even before Marvin J. Chomsky’s series Holocaustwas shown on television in 1978, the director had already brought Roots, a multipart series about the enslavement of blacks, to market in 1977. It won some of the most coveted television prizes in the United States, including nine Emmy Awards, a Golden Globe, and the Peabody Award. Concomitantly, for the first time, there were widespread calls to recognize the persecution and murder of Sinti and Roma under National Socialism as genocide. Other minorities also demanded recognition of their suffering.

Closely related to this, collective self-images also changed. Until the 1970s, they were often modeled primarily, though never exclusively, on the nation-building of the nineteenth century. In other words, they were mediated by heroic founding events: the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest, the Glorious Revolution, George Washington’s crossing of the Delaware. However, experiences of discrimination, persecution, and exclusion also gained greater importance even here as a result of the changed perception of the figure of the victim. Ever since, some nations have also seen themselves more strongly than before as emerging from a founding catastrophe: “the Armenians on the 1915 genocide, Ireland on the Great Famine from 1845 and 1852, Ukraine on the Holodomor . . . Rwanda on the extermination of the Tutsis.”¹⁸

In the course of the socioeconomic and cultural developments of recent decades, this process has both accelerated and intensified, both collectively and individually. The figure of the victim has become universalized. In other words, while claims of victimization were previously often a part of one’s self-understanding, they now frequently became central to the much-discussed “identity”—a fashionable term in political and social science that also became popular in the 1970s.

5

It is these self-understandings or “identities” mediated through the figure of the victim that are challenged by the Holocaust. This applies in many respects and at various levels. Let us first consider Edward Said’s Orientalism. In his magnum opus, Said uses the example of the Middle East to show that the Western view of this region has always been determined by a need for dominance. As evidence for this, he invokes French and British Orientalism of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, in particular the work of the Islam scholar Ernest Renan.

Critics such as Bernard Lewis pointed out early on that some of Said’s central theses, especially the victim narrative, are not scientifically tenable. They were able to show that European Oriental studies were by no means exclusively hostile toward their research subject. In particular, German-speaking scholars from the Habsburg Empire, the German Empire, and their successor states approached Islam without suspicion from the end of the nineteenth century and attempted to describe it from an internal perspective. For many of them, what Lewis once wrote in a different context was true: they were among the first “to stress, to recognize, and indeed sometimes to romanticize the merits and achievements of Muslim civilization in its great days.”¹⁹ In Orientalism, these scholars are systematically left out.

There is a purpose behind this: Said’s book seeks to place Israel in the continuity of colonialism, while presenting the Palestinians as its victims. It culminates in the insinuation that the Jewish state is a central representative of today’s Orientalism.

A look at the German role in the Arab-Islamic world would challenge Said’s theses in several ways. The Middle East was by no means only viewed as a sphere of influence by France and Great Britain, as is suggested in Orientalism. Wilhelmine Germany also maintained close relations with the region. The Weimar Republic and the Third Reich continued these relations in different ways. In particular, the National Socialist relationship with the Middle East was certainly not based solely on geostrategic plans. At least some of the leading Nazis, including the by no means insignificant Heinrich Himmler, did not so much see the Orient as the “other,” as Said suggests, but rather believed they recognized a spiritual kinship.²⁰ Such affinities are partly what underpinned the alliance between the Third Reich, Arab nationalists, and proto-Islamists that emerged in the 1930s and was destined to have a long afterlife.

But above all, the reference to Germany’s ties to the Middle East invokes the Holocaust, which also does not fit into Said’s scheme at all. Anyone who speaks of Germany and Israel, whether they want to or not, also addresses the extermination of European Jews. This is an event that cannot appear in Said’s work even if only because it refutes the notion that Israel is a product of colonialism. The international community agreed to the founding of the Jewish state in 1948 primarily because of the Nazi mass extermination. Israel was not founded in response to pressure from the old colonial powers, but against their will. France and Great Britain did not want to worsen their complicated relationship with the Islamic world by supporting the Jewish state.

As Middle East scholar Andreas Harstel shows in the Hallische Jahrbücher in 2021,²¹ all of these questions are concentrated in the memory of the German-speaking scholars of Oriental studies. Many of them came from Jewish families. Among the Jews of the German Empire and the Danube Monarchy, a great interest in the Orient had developed since the nineteenth century. It was often characterized less by arrogance than by the desire to better understand the region from which the religious traditions of Judaism originated. This applies to Moritz Steinschneider as well as Ignaz Goldziher, two founders of modern Islamic studies. Both of them were among the greatest critics of Ernest Renan, whom Said names as a prime example of Orientalist thought.

The lives of the Jewish scholars also evoke the event that is not allowed to take place in Said’s work. Steinschneider and Goldziher died before the Holocaust; Max Bravmann, Paul Kraus, and others, however, emigrated from Germany after the transfer of power to Hitler. Kraus was given a job in Cairo but lost it again in 1944 due to increasing antisemitism in Egypt. As his hopes for a new position in Jerusalem were not fulfilled, he committed suicide.

Said has to omit these experiences and overemphasize the influence of France and Great Britain because this is the only way to portray Israel as a product of Western supremacist thought, which turns the Arabs into victims. Orientalism, as Andreas Harstel puts it, is a “polemical pamphlet [Kampfschrift] transposed into academia.”²²

Even without going that far, it is hard to overlook the fact that the book targets the delegitimization of Israel, at least in its subtext. In his book The Question of Palestine, which was published one year after Orientalism,²³ Said himself ultimately placed his academic work in the context of his political engagement against Israel. Through both texts, the theoretical and the political manifesto, the affective investment in the Jewish state inscribes itself into postcolonial theory—albeit only in passing.

6

But even beyond the Middle East, the self-understandings or “identities” that are conveyed through the figure of the victim are challenged by the annihilation of the European Jews. Said’s unease in dealing with the Holocaust can be seen as part of a larger structure of defensiveness and resentment. Due to the existential horror that emanates from the mass extermination, it is linked to a narcissistic injury. It goes far beyond the “Question of Palestine” that Said is talking about. This injury is directly related to the distinctive nature of the Holocaust itself. The great crimes with which humanity was confronted before the extermination of the European Jews were all expressions of instrumental reason, which Max Horkheimer first discussed in the 1940s.²⁴ In this view, humans and nature are considered solely from the point of view of utility—and for this reason, among others, it sometimes veers into the irrational. Even the most horrific massacres of the colonial campaigns, however close they may have come to the crimes of National Socialism, and the “blood pump” of the First World War were still to some extent connected with the pursuit of power, influence, sales markets, increased prestige, or, not to be underestimated, gains in pleasure.

Not so the Holocaust: the annihilation of the European Jews was not the ultimate extension of the boundaries of instrumental reason, but rather a transgression of them. The indiscriminate extermination of women, men, children, and the elderly, anywhere in the world, regardless of whether they were unruly or willing to cooperate, able to work or infirm, essential to the war effort or not, can no longer be grasped by the categories of instrumental reason. On the whole, the Holocaust had nothing to do with the pursuit of power, influence, markets, prestige, or even pleasure. Instead, it was aimed at redemption, a notion that was only incompletely transferred from the sacred to the secular. The historian Saul Friedländer therefore also speaks of National Socialism’s “redemptive antisemitism.”²⁵

The drive for redemption and annihilation went so far as to eliminate the perpetrators’ own sense of self-preservation: Jewish forced laborers who had been classified as essential to the war effort were deported from the workbench to be murdered; the railway cars used to transport Jews to Auschwitz, even from the most remote Greek islands, were needed by the Wehrmacht for supplies. This elimination of the collective self-preservation instinct of the perpetrators was something completely new.²⁶

This particularity of the Holocaust has far-reaching consequences for the relationship to other genocidal events. For to the extent that the Holocaust went beyond the boundaries of instrumental reason, not pushing them to the extreme but rather breaking them, it eclipsed other mass crimes—not morally, of course, but epistemically. “Jewish suffering has become the benchmark, and the Shoah the founding event,” as the nouveau philosophe Pascal Bruckner once put it.²⁷ The Jews became the epitome of the victim.

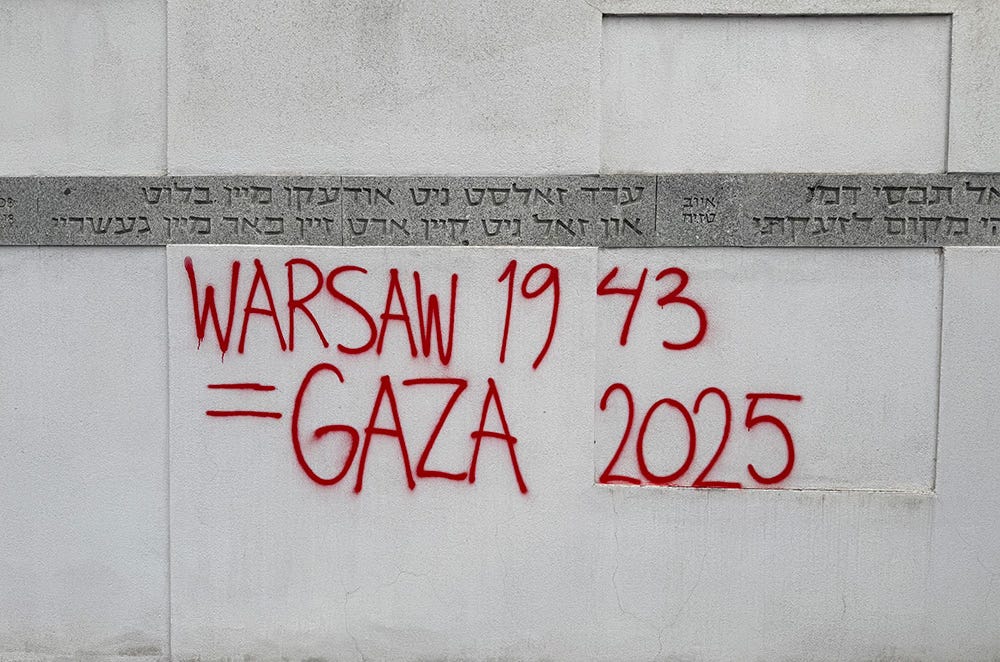

This triggers resentment and covetousness, especially in view of the fact that the social figure of the victim has assumed an ever greater significance in collective self-images. A few years ago, Peter Novick spoke of “Holocaust envy” and Edward Alexander of an attempt at “stealing the Holocaust.”²⁸ In view of the limited public attention, the need to have one’s own suffering recognized, and probably also the limited financial resources made officially available for compensation, a double urge has arisen. On the one hand, it aims to minimize the dimensions of the Holocaust and, on the other, to bring the victims’ own experiences closer to the Holocaust. This is done not least by translating one’s own suffering into the language of the extermination of the Jews—for example, when the partition of British India in 1947, which was associated with millions of expulsions and hundreds of thousands of deaths, is termed in a popular book “Bengal’s Hindu Holocaust,” or when Israel is accused of “fifty Holocausts” against the Palestinians, as Mahmoud Abbas did some time ago during his appearance at the German Federal Chancellery.²⁹

|

This double urge is reinforced by one of the basic assumptions of postcolonialism. It goes back to W.E.B. Du Bois, probably the most important civil rights activist in the United States. At the first Pan-African Conference in London in July 1900, the sociologist, historian, and philosopher declared that the central “problem of the twentieth century” was the “problem of the color line,” the boundary between skin colors.³⁰ As he later explained, during his travels through Europe he became familiar with the social question, discrimination against Poles in the eastern territories of the German Empire, and antisemitism.³¹

Yet for many postcolonial “scholars and activists,” the “color line” remains the central axis of conflict in world history, even more than fifty years after Du Bois’s death. This notion is also put into question by the Holocaust. The European Jews were not murdered because of their skin color; the crime of the century cannot be explained by references to the “color line” that was declared the central conflict of the century. This also results in both the postcolonial attempts to relativize the Holocaust and the questionable efforts to still classify the crime according to the color scale. Some postcolonial thinkers go so far as to identify Jews as “people of color” who only became “white” after their rise to the middle classes. Others try to establish the founding of Israel as the turning point from Jewish “blackness” to its “whiteness.” Empirical evidence is adjusted to fit the theory.

7

And now I come to my main point: the epistemic particularity of Jewish victimhood and the associated difficulty of categorizing the Holocaust on the basis of the “color line” bring older tones of resentment to the fore. They touch on deep-seated motifs of the collective unconscious. If we are to believe Freud, antisemitism also has roots in the history of religion. As David Nirenberg’s major study on the emergence of hostility toward Jews also suggests,³² these roots go back to the formative phase of monotheism.

The primitive accumulation of antisemitism is not least related to the theologically controversial question of whether the Jews are the chosen people of God. “I venture to assert,” Freud wrote in 1939 in Moses and Monotheism, “that the jealousy which the Jews evoked in the other peoples by maintaining that they were the first-born, favourite child of God the Father has not yet been overcome by those others, just as if the latter had given credence to the assumption.”³³ The hatred, resentment, and accusations that historically resulted from this regularly revolved around the demarcation from other religions, the refusal to accept conversion, and the—often only recently imposed—renunciation of missionary work: in other words, the seemingly particularistic aspects of Judaism.

Wrapped in contemporary notions of “universalism” and “particularity,” “homogeneity” and “difference,” some of these motifs have survived into the present day. This applies not least when the corresponding theories are impregnated with Islam or, as in the case of Edward Said or Achille Mbembe, a former student of the Dominicans, with Christianity. Mbembe, among others, argues that while Judaism is a religion of “exclusivism” and a “logic of closure,” Christianity has endeavored to “transcend exclusion,” to abolish the “distinction between Jews and Gentiles,” and to declare “any exclusion based on ethnic origin meaningless.”³⁴ The religious prejudice lingers on. Through the Holocaust, the theological notion of God’s chosen people was eventually negatively transferred into the sphere of the material world. The Jews were horrifically singled out: they became, as Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno bitterly commented in Dialectic of Enlightenment, truly “the chosen people.”³⁵

It almost seems as if this has also doubled the traditional resentment of the seemingly particularistic components of Judaism, the envy and jealousy of its supposed peculiarity. Paradoxically, the Holocaust became the catalyst of the old and the source of a new hostility toward Jews—an antisemitism not only despite but also because of Auschwitz. This is another reason why the viewpoint on the Holocaust and Israel, which was founded not least as a reaction to the mass extermination, is often just as limited as it is rigid; this is also why the zeal, the desires, and the successes of the propaganda that emanates from them are so great: new resentments encounter old idiosyncrasies and mutually reinforce each other. This is another reason for the limits of enlightenment, as described by Adorno and Horkheimer in the Dialectic of Enlightenment.³⁶

8

I will conclude with a summary. The developments we are currently experiencing certainly have many causes. Yet they also stem from many changes in social values and role models. Despite all the historical accusations, the silent hero was a social role model for the future until well after the Second World War, but in the 1970s it fell into crisis. This created a greater interest in the experiences of victims, discrimination, and marginalization, which until then had not only been overshadowed by individual and collective heroic narratives but had also often been frowned upon.

The decline in the significance of the hero initially had little to do with the Holocaust or the end of colonialism in its manifest form. It was rather due to the economic, political, and sociocultural changes brought about by the upheavals of the 1970s. Just as the retreat of the social figure of the hero suddenly created space for the articulation of victim experiences, this space also offered the opportunity to engage more intensively with the Holocaust than before. The same applies to other mass crimes. That Marvin J. Chomsky’s Holocaust premiered in the same year as Edward Said’s Orientalism was surely a coincidence. Yet the two works belong to the same historical context, however different or even contrary they may be.

Today, the interest in victims and the experience of being victimized has become universal, more than forty years after the first broadcast of the television series and the publication of the book. As I have tried to show, this is due not least to the change in self-images and role models that was directly linked to the hero’s retreat. While for a long time they had often been imbued primarily with heroism, since the 1970s experiences of exclusion and discrimination have also acquired a much greater significance for individual and collective self-understanding than before. The talk of “identity” that emerged during this period, as well as the at least partial retreat of universalism, did the rest: they stand for a growing interest in self-localization.

The interpretative struggles that have been waged for several years around the relationship between National Socialism and colonialism, as well as the sometimes surprising approval that postcolonial relativizations of the Holocaust have received, suggest that we are currently experiencing the beginning of the end of the history of Holocaust memory. This history of Holocaust memory began, strictly speaking, with the social significance of the figure of the victim; its end is not least (but also here: by no means exclusively) related to its dialectic. It results from a process of reversal. Or to put it another way, the current erosion of the memory of the Holocaust and the realization of its epistemic dimensions is, paradoxically, the result of a development to which it owes its emergence from the shadow of the memory of the war and of its resistance in the first place.

Jan Gerber is a historian and political scientist. He heads the “Politics” research department at the Leibniz Institute for Jewish History and Culture – Simon Dubnow (Dubnow Institute) in Leipzig and is an honorary professor of modern and contemporary history with a focus on modern Jewish history at the University of Leipzig. His latest publications include “Late Stalinist Antisemitism: An Approach to the 1952 Slánský Trial in Prague,” Center for Antisemitism and Racism Studies Working Papers 022; and “National Socialism and Colonialism: The Barbie Trial as a Primal Scene of Competing Memories,” in On the Critique of Identity, ed. Ivo Ritzer (Stuttgart: J. B. Metzler, 2025), pp. 137–54. He also edited the volume Die Untiefen des Postkolonialismus, Hallische Jahrbücher, no. 1 (Berlin: Edition Tiamat, 2021). This summer, Edition Tiamat will publish a book by him on the changes in the memory of the Holocaust.

Topics: Israel Initiative • TPPI Translations

Anthony Burgess, 1985 (Boston: Little Brown & Co., 1978).

Edward W. Said, Orientalism (New York: Pantheon, 1978).

Holocaust: The Story of the Family Weiss, directed by Marvin J. Chomsky, aired April 16–20, 1979, National Broadcasting Company (NBC).

Axelle Kabou, Et si l’Afrique refusait le développement? (Paris: Edition L’Harmmattan, 1991); George Ayittey, Africa Unchained: The Blueprint for Development (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004).

Compare Hanna Krall, Shielding the Flame: An Intimate Conversation with Dr. Marek Edelman, the Last Surviving Leader of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising (New York: Henry Holt and Co., 1986 [1977]).

Marek Edelman, Getto walczy: Udział Bundu w obronie getta warszawskiego (Warsaw: Wydawnictwo CDN, 1945). See Marek Edelman, The Ghetto Fights (New York: American Representation of the General Jewish Workers’ Union of Poland, 1946).

Ibid.

Tom Segev, The Seventh Million: The Israelis and the Holocaust, trans. Haim Watzman (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1993), p. 8.

Svenja Goltermann, Opfer: Die Wahrnehmung von Krieg und Gewalt in der Moderne (Frankfurt am Main: S. Fischer, 2017).

Christopher Lasch, The Culture of Narcissism: American Life in an Age of Diminishing Expectations (New York: W. W. Norton, 1978); see also Lasch, The Minimal Self: Psychic Survival in Troubled Times (New York: W. W. Norton, 1984).

Jean-François Lyotard, The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge, trans. Geoff Bennington and Brian Massumi (Minneapolis: Univ. of Minnesota Press, 1984).

Peter Novick, The Holocaust in American Life (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1999), p. 8.

In this regard, see generally Goltermann, Opfer.

Krall, Shielding the Flame, p. 9.

Ibid.

Edward Said, “The Quest for Gillo Pontecorvo” [1988], in Reflections on Exile and Other Essays (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ. Press, 2002), p. 283.

Bernd Kiefer, “Die Schlacht um Algier,” in Filmgenres: Kriegsfilm, ed. Thomas Klein et al. (Stuttgart: Reclam, 2006), p. 198.

Pascal Bruckner, An Imaginary Racism: Islamophobia and Guilt(Cambridge: Polity, 2018), p. 74.

Bernard Lewis, Islam in History: Ideas, People, and Events in the Middle East (Chicago: Open Court, 1993), p. 12.

See David Motadel, Islam and Nazi Germany’s War (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 2014).

Andreas Harstel, “Das Gründungsdokument des Postkolonialismus: Edward Saids Orientalism und Israel,” in Hallische Jahrbücher, no. 1, Die Untiefen des Postkolonialismus, ed. Jan Gerber (Berlin: Edition Tiamat, 2021), pp. 184–97.

Ibid., p. 188.

Edward W. Said, The Question of Palestine (New York: Vintage Books, 1979).

See Max Horkheimer, Eclipse of Reason (New York: Oxford Univ. Press, 1947).

Saul Friedländer, Nazi Germany and the Jews: The Years of Persecution, 1933–1939 (New York: Harper Perennial, 1997).

Dan Diner, Beyond the Conceivable: Studies on Germany, Nazism, and the Holocaust (Berkeley: Univ. of California Press, 2000), pp. 130–37.

Bruckner, An Imaginary Racism, p. 74.

Novick, The Holocaust in American Life; Edward Alexander, “Britain’s Academic Left Expunges Jews from the Holocaust,” The Algemeiner, October 6, 2019.

Sachi G. Dastidar, Bengal’s Hindu Holocaust: The Partition of India and Its Aftermath (Gurugram, Garuda Prakashan Pvt. Ltd., 2021); “Abbas wirft Israel ‘Holocaust’ an Palästinensern vor—Scholz empört,” Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, August 17, 2022. See likewise Sam E. Anderson, Black Holocaust for Beginners (Danbury, CT: For Beginners LLC, 2007); Del Jones, The Black Holocaust: Global Genocide (Philadelphia: Eye of the Storm Communications, Inc., 1992); Timothy White, The Black Holocaust (New York: Uptown Media Joint Ventures, 2020).

W.E.B. Du Bois et al., “To the Nations of the World,” in W.E.B. Du Bois: A Reader, ed. David Levering Lewis (New York: Henry Holt & Co, 1995); W.E.B. Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk [1903] (Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 2007).

W.E.B. Du Bois, “The Negro and the Warsaw Ghetto,” Jewish Life 6, no. 7 (1952): 14–15.

See David Nirenberg, Anti-Judaism: The Western Tradition (New York: Norton & Company, 2013).

Sigmund Freud, Moses and Monotheism, trans. Katherine Jones (London: Hogarth Press, 1939), p. 147.

Achille Mbembe, On the Postcolony (Berkeley: Univ. of California Press, 2001), p. 219.

Max Horkheimer and Theodor W. Adorno, Dialectic of Enlightenment: Philosophical Fragments, ed. Gunzelin Schmid Noerr, trans. Edmund Jephcott (Stanford, CA: Stanford Univ. Press), p. 137.

Ibid.

No comments:

Post a Comment